Edition 01. Harley Hamilton

We recently had the pleasure of visiting Harley Hamilton in his studio,

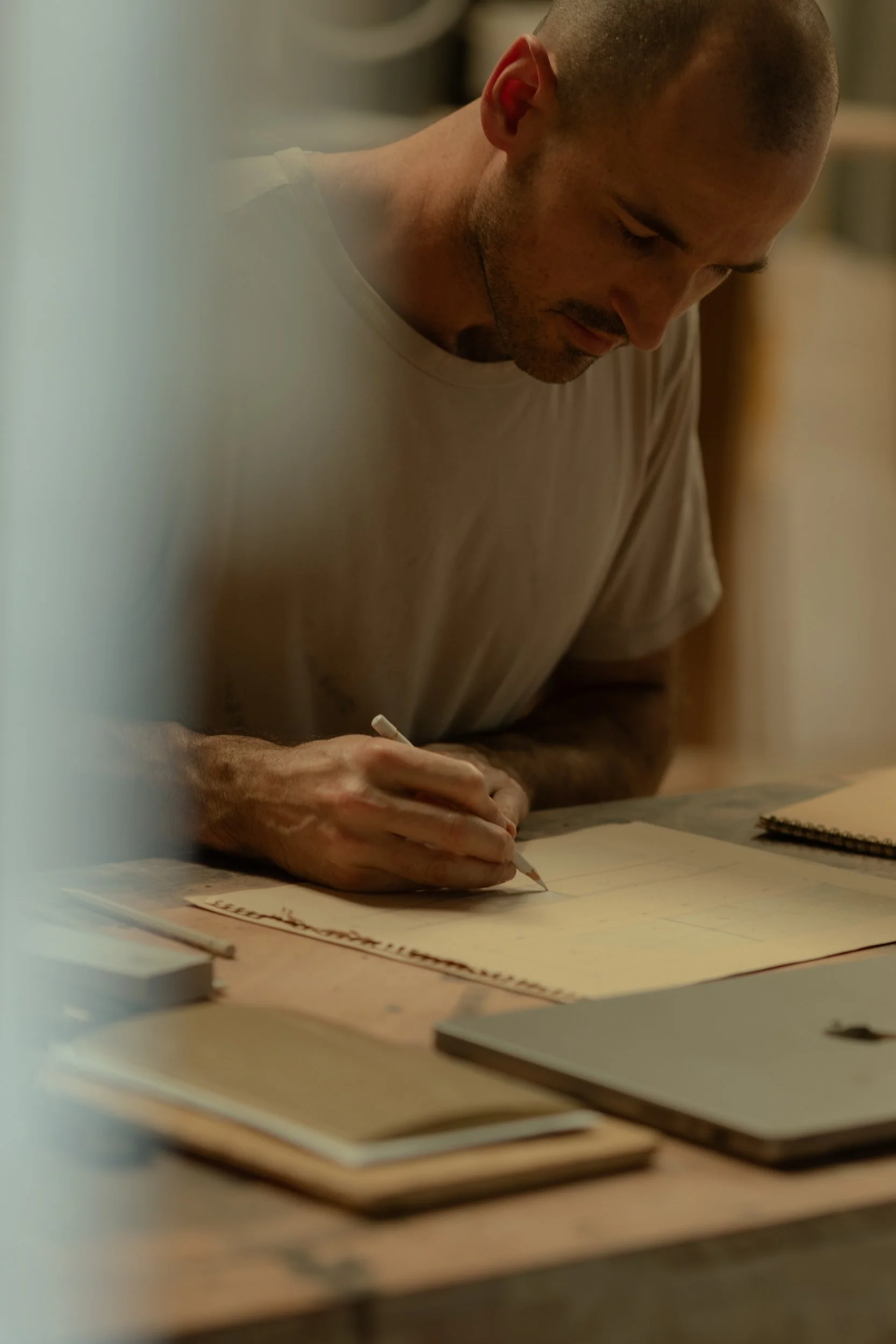

…A humble yet practical converted mechanics workshop on Bundjalung Country, Clunes NSW. Inside its walls Harley experiments with form and function with meticulous detail, taking raw materials including stone, cement, and fiberglass and turning them into one-off pieces of furniture. A true alchemy of elements, each piece requires a careful consideration of variables such as temperature and timing.

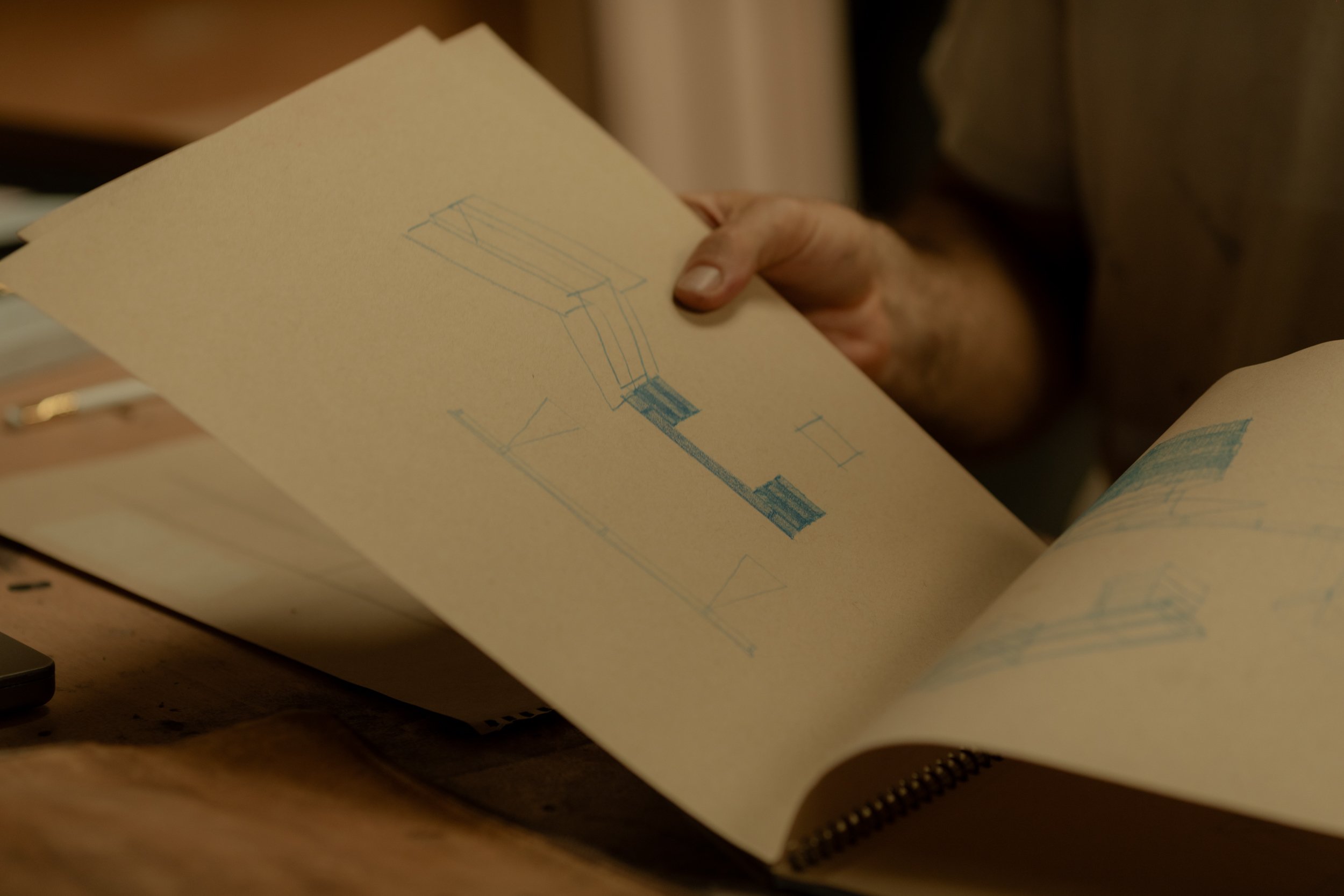

Harley’s background and formal study in architecture coupled with his experience in building has laid the groundwork for his current pursuit of furniture making. With subtle reference to the ancient craft of mosaic, Harley puts a contemporary spin on stonemasonry through his thoughtfully constructed designs. It is always fascinating to witness an artist build something from scratch, and Harley does just that throughout the entire process. From the initial hand-drawn sketches to mixing pigments, laying stone, and building formwork, the final output is a testament to Harley’s patience and craftsmanship.

MM. Can you walk us through the basic process of cast concrete furniture?

HH. A fair bit of time goes into the formworks and molds before a piece gets under way, sometimes requiring a prototype in a material that is easier to work first, from which I can then shape a formwork around. The concrete is cast within these.

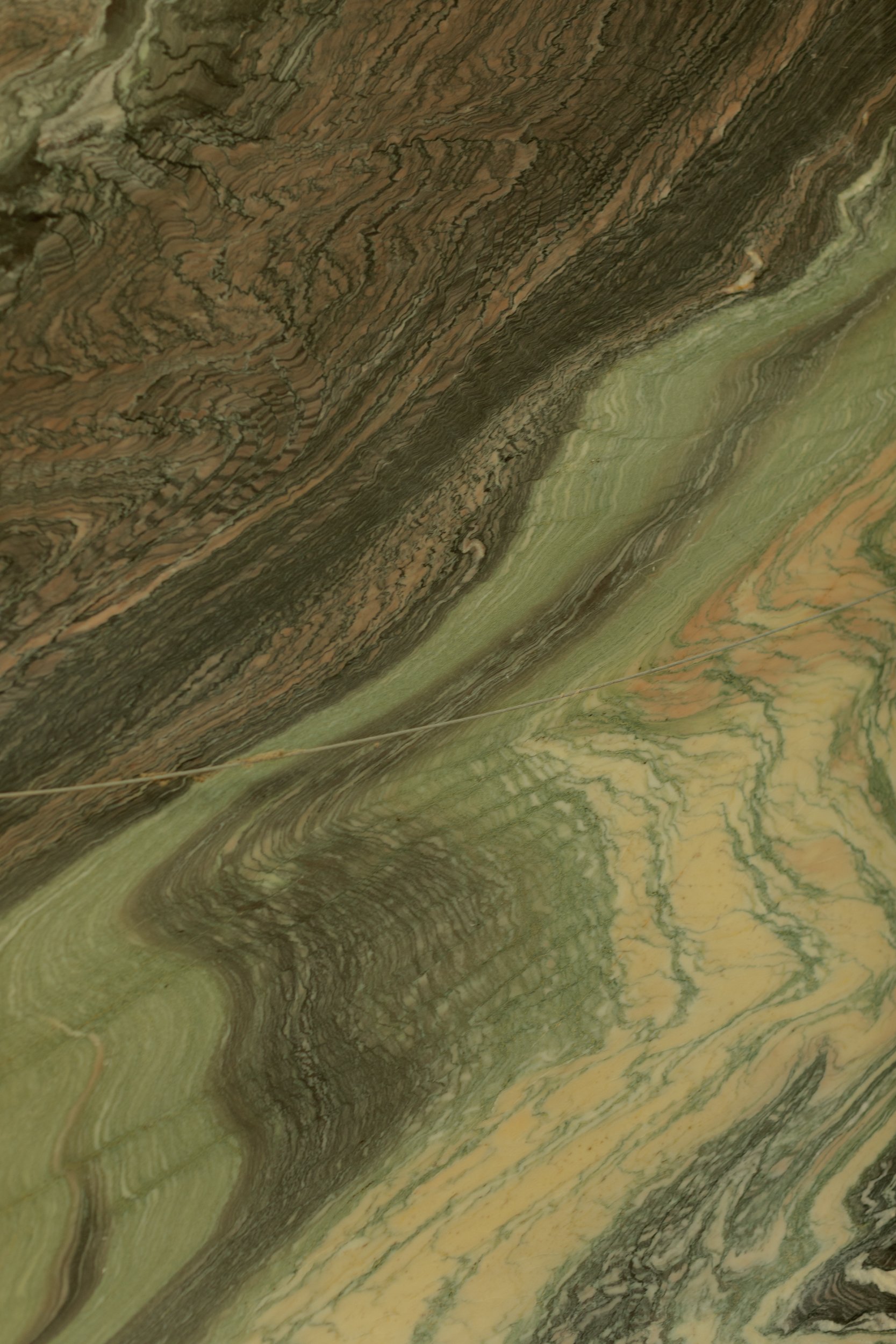

You can vary the concrete mix endlessly which is fun and achieve just about any colour by adding oxides, and the consistency and texture can be affected by adding more or less of some ingredients yielding very different results in the finished surfaces.

The poured concrete then needs to be left to cure. Depending on how well the formworks are built affects the extent to which you need to cut and polish the piece later on. Lastly, each piece is sealed.

It's a joy because you get to create a material from scratch that differs at least subtly each time it is poured, so there is always an element of surprise.

MM. With so many variables to manage within each step, what would you say is the most difficult part of the process to get right consistently?

HH. Probably the managing curing. You're making a new material so it wants to move. If you don't manage the curing conditions correctly or for long enough the work will bow, warp or crack as it heats up and then cools and sets.

MM. You mentioned when we spoke in person that early in the journey you went through a period of trial and error.

How did you find the best way to navigate this process?

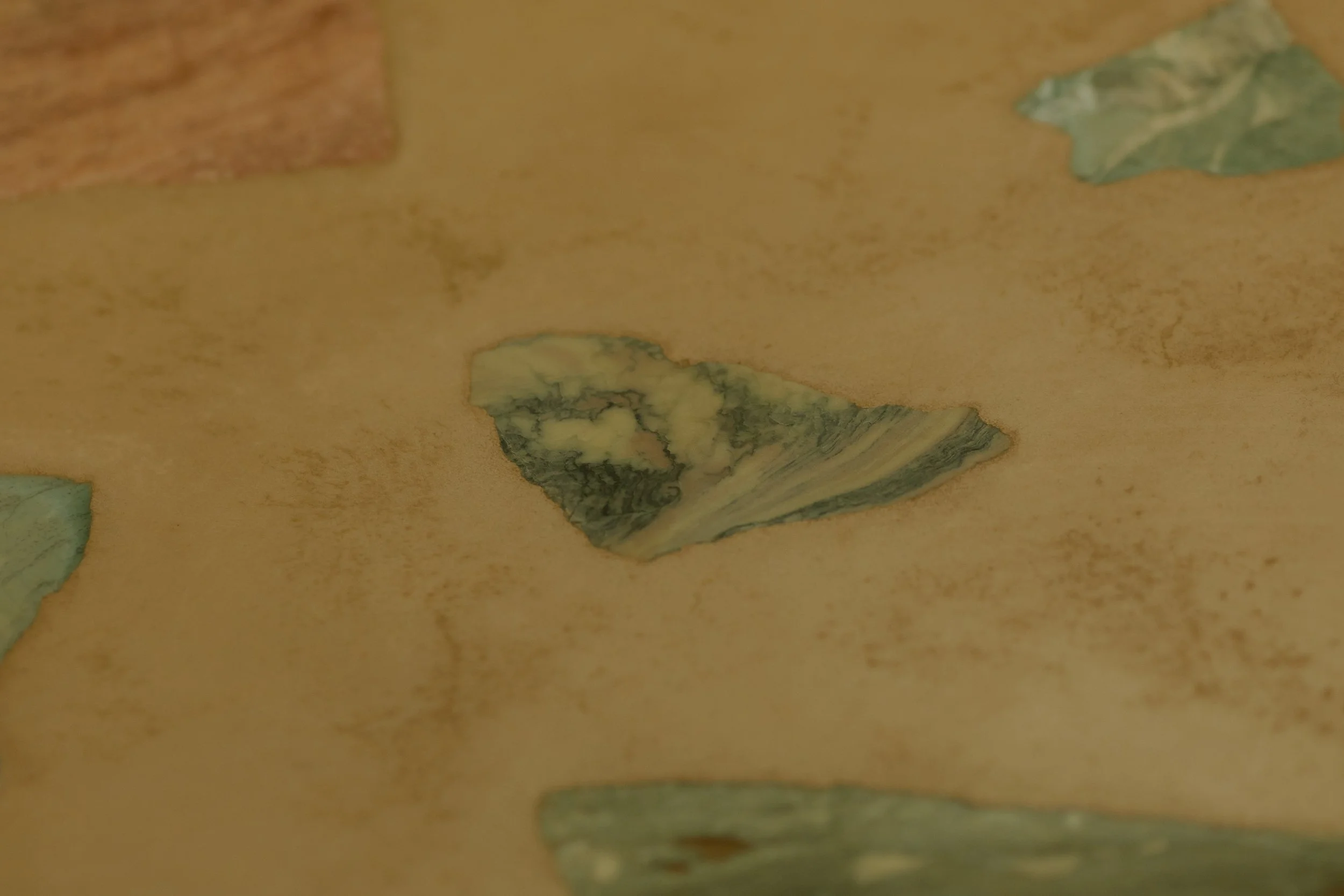

HH. Any time I've started working with a new material I've found it to be a humbling experience and concrete is no different, it is not inert, as I first thought when I started experimenting with it in furniture. And I was adding large sections of stone to the mix, the marriage of which affected the way the concrete 'behaved'.

Typically a mosaic table has a substrate onto which the tiles are laid, or large stone fragments were laid Palladiana style on top of a stable floor, whereas I was trying to make the two materials work together as a single structure. There weren't a lot of precedents that I was aware of at the time. But I had a clear idea of what I wanted to make and I think that goes a long way when you hit hurdles along the way.

MM. You studied architecture at RMIT in Melbourne. What eventually lead you to furniture design?

HH. I went into construction after uni as I wanted to see things taking shape on site and be a part of it. From there I found work in the crafts and trades looking to get a better handle on various materials and how to design for them, and work with them.

I really just wanted to know the ins and outs of architecture and construction from as many angles as possible. Around this time I began paying more attention to furniture and liked seeing how it would make its way into people's houses under the guise of function, but would take on a fundamental role in the creation of a home, particularly over time and through everyday use, and I think I always wanted to be more closely engaged in the creation of homes rather than structures.

We can have a tendency to overlook the significance objects hold, but a house is essentially uninhabitable until we are supported in our day to day routines by these emotional and functional aids.

MM. What do you carry with you most from your architecture studies?

HH. Architecture is defined by constraints, and how we respond to them. The variables that clients, collaborators, budget changes and working within a specific context is a significant part of the creative process for me. It helped me see that the challenges in a project will sometimes lead to the most unique part of a design by necessitating inventive and unexpected solutions.

It also gave me a respect for the difficulty in designing something that has clarity, or appears effortless, because most briefs are complex, so making a design appear complex is easy.

MM. Furniture design seems like the perfect amalgamation of your previous experience.

Are you content with where you are at creatively or do you feel there is another adaptation to come?

HH. I'm happy doing this right now. The balance between making and designing is a joy. I think it's just that which I'll try to maintain. I like having materials and half finished things on the go in the workshop as it often leads to new ideas, and that alone will take my work somewhere else.

MM. Your reference to the ancient craft of mosaic is often a key feature of your designs.

What is it about the mosaic that prompted you to integrate it within your work?

HH. It was actually seeing archaic mosaic floors that were only partially intact, where disembodied elements were suspended in vast swaths of the restoration team's neutral infill render, rather than a complete full image that I first found a connection to in my work.

The incomplete and imperfect patches of remaining tile work were given greater emphasis and the space between left me free to guess and fill in the gaps with my own thoughts.

I have a habit of wanting to give all the individual and separate elements of a design equal space and attention. I also was drawn to it’s long and storied tradition and attempting to participate with it in a way that feels relevant today, and making something that could truly last.

MM. As a father of two young ones, how have you found a sense of balance in your work and life day to day?

HH. I didn’t have much balance before kids - I was lucky that I liked my work but that is really all I did - and I think it took having a family to show me that it was not sustainable. I try now to be conscious that if I want my kids to know how to look after themselves I need to role model it.

MM. What’s next for you in the Harley Hamilton Studio?

HH. There are some pieces that I am trailing in a material that is new to me, I've not worked with it much so I'm looking forward to seeing how those come together. Things also appear to be gradually scaling up in size, and I like working large so I'll look forward to seeing how big things end up.

HARLEYHAMILTON.COM

@HARLEYHAMILTONSTUDIO

Words. Rachel Thatcher

Images. Zali Rae